What is Raw Feeding? Who thought the idea up, anyway?

By Rachel Kanarek

Since the 1980s, there has been an extraordinary movement in the companion animal community. Slowly, many of us have progressed from feeding kibble towards feeding whole, unprocessed foods to our pets. The events of the past five years have greatly precipitated this movement, as countless pet foods – even those considered “high quality” – have been recalled due to unsafe ingredients and storage conditions that ultimately led to a number of animals getting sick and even dying.

Personally, feeding a home-prepared diet to my dogs always seemed like the right thing to do. Having been raised by a stay-at-home mother from an immigrant family, I never ate a microwave meal until I was in my teens, and fast food restaurants were out of the question. I simply wanted to feed my dogs (my “children in fur coats”) the same way my mother fed me. So, when I acquired my first Manchester Terrier in 2003, it only made sense to wean him off the kibble his breeder generously supplied and onto a raw diet.

Since the 1980s, there has been an extraordinary movement in the companion animal community. Slowly, many of us have progressed from feeding kibble towards feeding whole, unprocessed foods to our pets. The events of the past five years have greatly precipitated this movement, as countless pet foods – even those considered “high quality” – have been recalled due to unsafe ingredients and storage conditions that ultimately led to a number of animals getting sick and even dying.

Personally, feeding a home-prepared diet to my dogs always seemed like the right thing to do. Having been raised by a stay-at-home mother from an immigrant family, I never ate a microwave meal until I was in my teens, and fast food restaurants were out of the question. I simply wanted to feed my dogs (my “children in fur coats”) the same way my mother fed me. So, when I acquired my first Manchester Terrier in 2003, it only made sense to wean him off the kibble his breeder generously supplied and onto a raw diet.

As with everything else in my life, including my choice of breed, I researched canine anatomy and genetics ad nauseam prior to bringing my little Monster Terrorist – I mean, Manchester Terrier – home, and it was this research that led me to feed raw with confidence. In the years since, as my confidence and knowledge have grown, I’ve shifted from pre-made raw (such as Nature’s Variety® or Blue Buffalo®) to whole prey model (“WPM”) raw. Through this series of articles, I will arm you with the same knowledge regarding canine anatomy, which will hopefully increase your confidence and enable you to feed a raw diet.

This article is the first in a series of three that, together, will (1) provide you with a strong foundation for raw feeding, and (2) more importantly, spur you to continue educating yourself (and others!) about WPM raw. In this issue, we will explore the beginnings and history of feeding our dogs – raw or otherwise. Next time, we will delve a bit deeper into canine genetics and anatomy, hopefully setting your mind at ease about the safety of a raw diet for your fur-kids. And finally, in part three, we’ll look at a simple guide to starting and maintaining a raw diet for the life of your pets. I realize I’m being optimistic in splitting this topic over three separate articles, but I believe that Black & Tan Magazine will be a raging success, and we’ll all be drooling in anticipation for the next issue. I hope I’m right! So, hold onto your hats, because here we go!

A lot of people view raw feeding with skepticism. To them, it’s like some newfangled “cult” that just sprouted up about 25 years ago. Why should they trust the health and wellbeing of their precious pets to such a new idea? Kibble is a “safe” and “known” product, and the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) says it contains the balanced nutrition our pets need. So why argue with that? After all, if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. Right?

Not really.

This article is the first in a series of three that, together, will (1) provide you with a strong foundation for raw feeding, and (2) more importantly, spur you to continue educating yourself (and others!) about WPM raw. In this issue, we will explore the beginnings and history of feeding our dogs – raw or otherwise. Next time, we will delve a bit deeper into canine genetics and anatomy, hopefully setting your mind at ease about the safety of a raw diet for your fur-kids. And finally, in part three, we’ll look at a simple guide to starting and maintaining a raw diet for the life of your pets. I realize I’m being optimistic in splitting this topic over three separate articles, but I believe that Black & Tan Magazine will be a raging success, and we’ll all be drooling in anticipation for the next issue. I hope I’m right! So, hold onto your hats, because here we go!

A lot of people view raw feeding with skepticism. To them, it’s like some newfangled “cult” that just sprouted up about 25 years ago. Why should they trust the health and wellbeing of their precious pets to such a new idea? Kibble is a “safe” and “known” product, and the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) says it contains the balanced nutrition our pets need. So why argue with that? After all, if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. Right?

Not really.

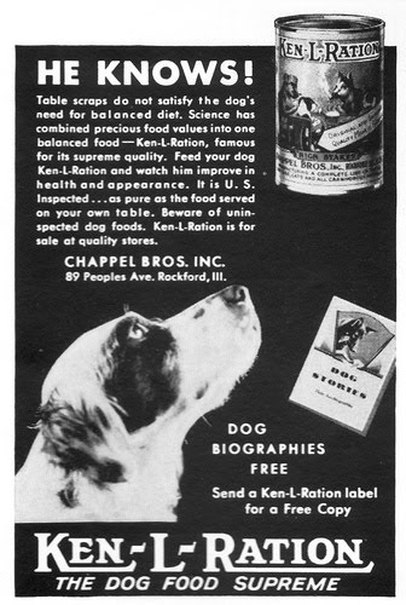

The truth is, the very first kibble-like product ever fed to dogs was a stale biscuit from a sea ship in the mid- to late-1800s. An electrician and salesman named James Spratt ran with the idea and mass-produced similar biscuits as cheap and easy dog food for the growing population of urban-dwelling pet owners. Kibble, as we know it today, was formulated after the First World War and didn’t become widely popular until after the Second World War, when the United States experienced an economic boom that enabled more families to keep companion animals. At the same time, comfort and convenience were being touted as the wave of the future. And kibble is certainly convenient…

The kibble industry continued to grow through the 1960s and 1970s, and kibble manufacturers worked very hard to convince consumers that table scraps were dangerous, unbalanced, unregulated sources of nutrition for pets. They had a product to sell, so they used a marketing technique known as “manufacturing doubt” to encourage people to buy what they were selling. If you tell people – often enough and loud enough – with bright shiny letters and big fancy billboards – that the alternatives are dangerous, they’ll be inclined to use the product you’ve convinced them is the only safe choice. Needless to say, it worked! Today, pet food is an $11 billion industry, and growing.

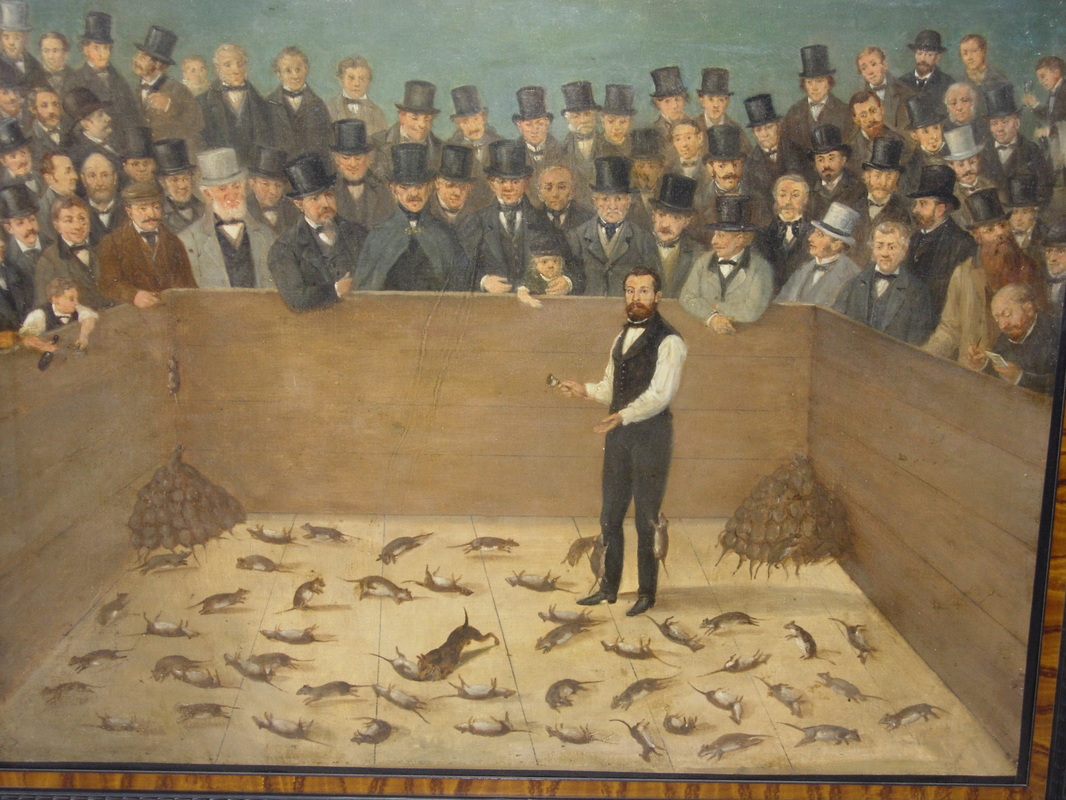

Given that dogs have been “man’s best friend” for at least 15,000 years (according to archaeological records), and kibble -- in any form -- has only been fed to dogs for about 150 years, it’s really the kibble that’s “newfangled.” Let me stress this, because it’s huge: dogs have eaten kibble for less than 1% of the time they’ve co-habitated with humans. Before the 1900s (i.e., for at least 99% of the time that dogs have lived with people), every dog ate whole, unprocessed foods, be they raw or cooked. Obviously, it was safe enough to enable the species to exist, thrive, and reproduce – because they’re still with us today.

Now ask yourself this: would l feed my children Total® cereal three meals a day, every day of their lives? After all, it’s got “total” nutrition… Would I feed my children Happy Meals® from McDonald’s® every day of their lives? It satisfies the food pyramid… If the answer is “no,” then we’re on the same page. Pre-packaged, nutrient-enriched dog foods are basically cereals for dogs: they may satisfy the nutritional requirements set forth by AAFCO, but so does a Happy Meal®. Like cereals, during the production process, kibble is cooked at such high temperatures that all the proteins, minerals, vitamins, etc., have been denatured, such that nutrients then have to be added back into the mix near the end of the production line. Those pretty pictures of whole meats, fruits, and grains that you see in the kibble commercials are a far cry from the product that reaches your dog’s food dish.

The kibble industry continued to grow through the 1960s and 1970s, and kibble manufacturers worked very hard to convince consumers that table scraps were dangerous, unbalanced, unregulated sources of nutrition for pets. They had a product to sell, so they used a marketing technique known as “manufacturing doubt” to encourage people to buy what they were selling. If you tell people – often enough and loud enough – with bright shiny letters and big fancy billboards – that the alternatives are dangerous, they’ll be inclined to use the product you’ve convinced them is the only safe choice. Needless to say, it worked! Today, pet food is an $11 billion industry, and growing.

Given that dogs have been “man’s best friend” for at least 15,000 years (according to archaeological records), and kibble -- in any form -- has only been fed to dogs for about 150 years, it’s really the kibble that’s “newfangled.” Let me stress this, because it’s huge: dogs have eaten kibble for less than 1% of the time they’ve co-habitated with humans. Before the 1900s (i.e., for at least 99% of the time that dogs have lived with people), every dog ate whole, unprocessed foods, be they raw or cooked. Obviously, it was safe enough to enable the species to exist, thrive, and reproduce – because they’re still with us today.

Now ask yourself this: would l feed my children Total® cereal three meals a day, every day of their lives? After all, it’s got “total” nutrition… Would I feed my children Happy Meals® from McDonald’s® every day of their lives? It satisfies the food pyramid… If the answer is “no,” then we’re on the same page. Pre-packaged, nutrient-enriched dog foods are basically cereals for dogs: they may satisfy the nutritional requirements set forth by AAFCO, but so does a Happy Meal®. Like cereals, during the production process, kibble is cooked at such high temperatures that all the proteins, minerals, vitamins, etc., have been denatured, such that nutrients then have to be added back into the mix near the end of the production line. Those pretty pictures of whole meats, fruits, and grains that you see in the kibble commercials are a far cry from the product that reaches your dog’s food dish.

On the heels of the widespread pet food recalls that occurred in the last five years, there is a growing awareness that the advertisements we are bombarded with on television and in print media do not reflect reality. An increasing number of pet owners have begun questioning the “manufactured doubt” the kibble industry has worked so hard to instill as fact in our consciences. For many people, interest in raw feeding begins with one very simple question: How can dog food manufacturers call their product safe if dogs are dying from eating it?

While skepticism towards kibble has increased, raw feeding has gained credibility through a number of important developments in research around the genetic roots of our furry friends and the effects that complex carbohydrates can have on their bodies.

The raw feeding movement gained significant momentum through the work of Tom Lonsdale and Ian Billinghurst in the late-1980s and early-1990s. Lonsdale and Billinghurst popularized the “bones and raw food” or “biologically appropriate raw food” (BARF) diet, which encouraged dog owners to feed their animals raw, unprocessed foods. Though they are often considered the “godfathers of raw feeding,” they were simply two in a long chain of educators who endorsed a holistic lifestyle for pets. As early as the 1930s, when kibble was first gaining a stronghold in the market, Juliette de Bairacli Levy, an herbalist and the pioneer of holistic veterinary medicine, was educating the public about the benefits of a natural raw diet.

Lonsdale’s and Billinghurst’s BARF diet – which is still successfully fed by many, and is certainly better than kibble – has slowly evolved into the WPM diet we will explore in this series. As you’ll read in coming installments of A Raw Feeding Primer, the major difference between the two is the inclusion (or exclusion) of carbohydrates. While the BARF diet is reverse engineered from kibble, and therefore includes carbohydrates, the WPM diet is formulated based on the analysis of what our dogs’ wild counterparts eat in nature, and therefore does not.

And that, in a nutshell, is why I feed WPM raw to my dogs: it’s only natural! Mother Nature thought it up, and she generally has a good head on her shoulders.

While skepticism towards kibble has increased, raw feeding has gained credibility through a number of important developments in research around the genetic roots of our furry friends and the effects that complex carbohydrates can have on their bodies.

The raw feeding movement gained significant momentum through the work of Tom Lonsdale and Ian Billinghurst in the late-1980s and early-1990s. Lonsdale and Billinghurst popularized the “bones and raw food” or “biologically appropriate raw food” (BARF) diet, which encouraged dog owners to feed their animals raw, unprocessed foods. Though they are often considered the “godfathers of raw feeding,” they were simply two in a long chain of educators who endorsed a holistic lifestyle for pets. As early as the 1930s, when kibble was first gaining a stronghold in the market, Juliette de Bairacli Levy, an herbalist and the pioneer of holistic veterinary medicine, was educating the public about the benefits of a natural raw diet.

Lonsdale’s and Billinghurst’s BARF diet – which is still successfully fed by many, and is certainly better than kibble – has slowly evolved into the WPM diet we will explore in this series. As you’ll read in coming installments of A Raw Feeding Primer, the major difference between the two is the inclusion (or exclusion) of carbohydrates. While the BARF diet is reverse engineered from kibble, and therefore includes carbohydrates, the WPM diet is formulated based on the analysis of what our dogs’ wild counterparts eat in nature, and therefore does not.

And that, in a nutshell, is why I feed WPM raw to my dogs: it’s only natural! Mother Nature thought it up, and she generally has a good head on her shoulders.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed